The Trullo

The Trullo

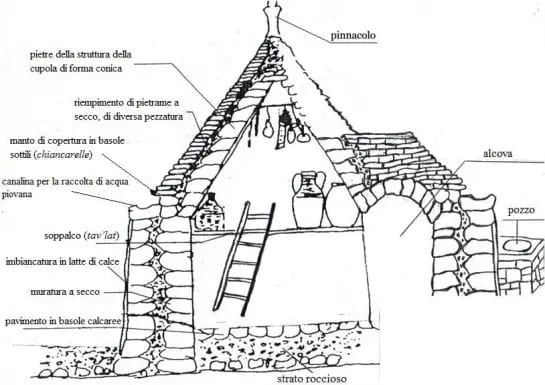

In this corner of Apulia, in the Itria Valley, the trulli, with their conical roofs and mysterious origins tell stories thousands of years old. Trulli are cone-shaped architectural wonders, generally consisting of a circular (the oldest) or quadrangular base. Their perimeter walls vary in height from 1.60 to 2 meters. Their thickness in the present day is no more than 80 cm, whereas at one time they ranged over 1 meter and often reached 2. On the walls rests the cone (the cannela), which rises narrowing to a culmination, indicated externally by a pinnacle.

The conical vault on the outside is covered with limestone slabs called chianche (or chiancole, chiancarelle), which also provide waterproofing.

They are arranged in overlapping rows, sloping outward to facilitate rainwater runoff. Both the walls and the dome are raised with drywall.

Trulli are the prime example of perfect insulation: warm in winter and cool in summer. This phenomenon is due to the formation of small air chambers between one chianca and another, which absorb changes in temperature, keeping it constant.

Interior plastering, in milk of lime on a layer of bole (red earth) containing straw, prevents insects from passing through and acts as thermal insulation. In addition, the so-called passivity of the structure (there are no binders in trulli) is able to absorb even the strongest earthquake tremors. The Trulli of Alberobello have been included by UNESCO in the list of protected properties as a world heritage site.

Although archaeological finds or foundations of huts dating back to the Bronze Age have been found in the areas of trulli development, there are no particularly ancient trulli, for one simple reason: rather than providing for the repair of a trullo, for economic reasons, it was demolished and rebuilt by reusing the material. Thus the present buildings date from around the 16th century, when Giangirolamo II Acquaviva D’Aragona, Count of Conversano, known as the “Guercio di Puglia,” one of the earliest feudal lords of the area, enforced the construction of dwellings only with dry stone and without the use of mortar. This expedient actually avoided the payment of taxes to the Spanish viceroy of the Kingdom of Naples since they were not considered as urban settlements, but rather as precarious constructions that were easy to demolish and therefore not taxable. The truth is that they have very little that is precarious; in fact, the structure provides remarkable stability, as well as ensuring optimal thermal balance.

Another very reliable theory concerning the origin of trulli links the Middle East with Apulia: there is in Turkey the village of Harran or, indicating by its ancient name, Caran composed of thousands of trulli. It was from Caran that the patriarch Abraham set out, two thousand years before the birth of Christ, to reach the land of Canaan with his people. The present Harran was rebuilt about a thousand years ago, corresponding to the Byzantine conquest of Apulia when, that is, some Jewish and Oriental communities settled between Bari and Taranto.

It is likely that it was at that time that trullo architecture was transplanted to Apulia; the trullo, therefore, according to this story, could even claim a ‘biblical origin.

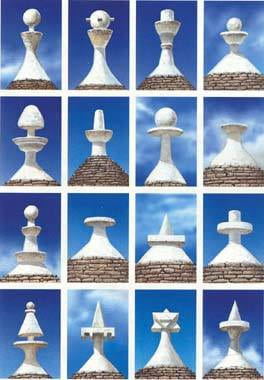

If we take this theory of the eastern birth of the trullo among Turkey, Syria, and Anatolia, areas notoriously prone to frequent and devastating earthquakes, the pinnacle is overwhelming evidence, in that, predominantly spherical in shape, in the Itria Valley, it was originally not fixed but only propped up so as to leave it free to “roll” down from the dome in the event of any telluric movement, so that the noise caused would allow the inhabitants of the trullo to get to safety in a timely manner: a caution certainly also imported from the East. In fact, if we look at pictures of the Harran trulli located in earthquake-prone area, we can see that they are all, indistinctly, topped by a pinnacle placed in equilibrium, which by plummeting definitely performs an “alarm” function in case of an earthquake.

The symbolism related to the trulli is illustrated by the pinnacles and emblematic figures drawn with lime milk on the dome. It does not so much chase away the evil eye, as many insistently think, as it conveys the magical-cultural value with which the trullo had to be born, as an image of heaven and as an altar for solar worship, and the pinnacle is nothing but the phallic image connected to this worship. Decorative pinnacles, also called cucurnei or tintulas, can take different forms, often inspired by symbolic, mystical, religious elements or traditional motifs. For some scholars, pinnacles are a kind of “mark,” placed by different trullar masters (builders) to distinguish their work, or a simple decorative element chosen by the owners of the house. For others, their origin can be traced to primitive magical symbolism. Not surprisingly, their characteristic shapes (the disc, sphere, cone, square- or triangular-based pyramid) in antiquity were connected to the betilic cults (from the Latin bactulos, sacred stone), practiced by primitive agricultural peoples and documented in Apulia as far back as the first century B.C., peoples who worshipped stone thinking it was the daughter of the sun and the stars. In more advanced forms, the pinnacle placed on the apex of the dome becomes a cruciform polyhedron, a starry polygon, a pyx surmounted by an orb. For these elements, in fact, as was the case with painted symbols, the original magical value would be replaced, progressively, by a Christian and therefore religious interpretation.

On the front of each dome are painted symbols, also, of propitiatory or magical value, whether of pagan or Christian origin. The symbols are drawn freehand with the use of lime, synonymous with purification (it is used as a disinfectant): the white color is reminiscent of that of milk and the whiteness of the trulli is reminiscent of something pure. In the past, the mayor of Alberobello could issue a lactation ordinance (from allattè, meaning to paint the walls white) to restore the trulli to their original color. Such symbols, made coarse because of the roof surface and the not always specific decorative skills of the painter, are often identifiable by intuition rather than clarity of design. Following a classification dating back to 1940, they can be divided into: primitive, magical, pagan, Christian, ornamental, and grotesque. This subdivision is purely indicative, and although its scientific validity is relative, it is functional for quick identification. According to the census there are more than two hundred different symbols between those still on the cones and those handed down by oral tradition. The classification and decoding of the symbols is still problematic because the tradition and use of the symbols occurs only orally, so no detailed explanation of what they mean has come to us.

In fact, although almost all symbols have acquired an eminently Christian meaning, the peasant cannot break away from their utilitarian and apotropaic purpose. Ancient folk belief considers these signs to be endowed with special magical virtues and capable of warding off evil influences.